Move Security - Lesson 1: Security Analysis of the Move Language – Game Changer of Smart Contracts

Author: Numen

Preface

Move language is a smart contract language that can be compiled to run in a blockchain environment which implements MoveVM. It was born with deep blockchain and smart contract security consideration in mind, and refer to some security design of RUST languages. How secure is it as a new generation of smart contract language with the main feature of security? Is it possible to avoid the security threats commonly found in other contract virtual machines such as EVM or WASM at the language level or related mechanisms? Are there any security issues specific to the language itself?

Numen Cyber Labs, in the process of researching two public chains that implement smart contracts based on MoveVM – APTOS and SUI, discovered some underlying vulnerabilities at the virtual machine level (https://medium.com/numen-cyber-labs/the-story-of-a-high-vulnerability-in-move-reference-safety-verify-module-2340f3d8c642 and https://medium.com/numen-cyber-labs/analysis-of-the-first-critical-0-day-vulnerability-of-aptos-move-vm-8c1fd6c2b98e) and have been officially confirmed and fixed.

This article will try to answer questions above at three levels: language features, runtime mechanisms, and verification tools.

1. Security Features of the Move Language

Writing the correct code is difficult, and even after many tests, we cannot guarantee that we are writing non-vulnerability codes. Writing code that maintains critical security properties when interacting with untrusted code is even more difficult. There are many techniques to enforce some runtime security: programming patterns such as sandboxing, process isolation, object locking, etc.; or, static security can be specified at compile time, such as mandatory static typing or assertion checking.

Sometimes, we can also resort to semantic analysis with static analysis tools to ensure that their code is consistent with the security rules, i.e., to ensure that some provable logical statute remains intact even when the code links to and interacts with untrusted code.

It looks like these are good solutions to avoid runtime overhead and to detect security issues in advance.

Unfortunately, however, programming languages are able to get extremely limited security by using these methods, which we ascribe to two reasons:

First, they usually have features in their languages that cannot use static analysis tools, such as dynamic dispatch, shared mutability, and nonlinear logic such as reflection, which violate security rules and thus give hackers a broad attack surface.

Second, they provide too much fixability that makes it hard to realize the third-party security tools. Therefore, most programming languages cannot be easily extended with security-related static tools or expressive specification languages. Although both types of extensions are essential and can be predefined.

Unlike many existing languages, the Move language is designed to support both writing programs that interact securely with untrusted code and static verification.The Move language has this security feature because it eschews all non-linear logic based on flexibility considerations, does not support dynamic dispatch, and does not support recursive external calls, and introduce some concepts such as generalization, global storage, and resources to implement alternative programming patterns. For example, dynamic dispatching and recursive omitted by Move but supported by Solidity have led to costly re-entry vulnerabilities in EVM.

To better understand the features of the move language, let’s look at the following sample program.

The realization of coin in Move.

a) Module

Each Move module consists of a set of structure types and procedures definitions. Modules can import type definitions (e.g., use 0x1::signer on line 2) and call procedures declared in other modules. The fully qualified name of a module starts with the 16-byte account address where the module code is stored (here, we write an account address, such as 0x1, as shorthand for a 16-byte hexadecimal address, padded with zeros). The account address acts as a namespace to distinguish between modules with the same name; for example, 0x1::TestCoin and 0x2::TestCoin are different modules with their own types and procedures.

b) Structs

There are 2 Structs in the module. A Coin represents the token assigned to the module user, while Info records the total number of tokens present. The has key syntax on the declaration shows that both structures are defined as resource types (structures with key or store Abilities), indicating that both structures can be stored in a persistent global key/value store.

c) Procedure (function)

The module defines an initialize, a safe procedure and an unsafe procedure. The initialize procedure must be called before any Coin is created, and it initializes the total_supply of the single instance Info value to zero. Here, signer is a special type that represents a user verified by logic other than Move. Asserting that the signer’s address is equal to ADMIN ensures that this procedure can only be invoked by the specified administrator account. The procedure mint allows the administrator to create the required number of new tokens (line 25); this is after the total number of coins has been updated (line 23). Like initialization, this procedure has access controls to ensure that it can only be invoked by the administrator account (lines 20 and 21). the value_mut procedure accepts a mutable reference to Coin as input and returns a mutable reference to the Coin value field.

As you can see, the contract structure does not differ much from other smart contract languages, but we need a more detailed explanation of the resource types and the concept of Persistent Global Storage, which is the key mechanism for storage security in the Move language.

Global storage allows Move programs to store persistent data (e.g., Coin balances) that can only be programmatically read/written by the module that owns it, but is also stored in a public ledger that can be viewed by codes running in other modules.

Each key in the global storage consists of a fully qualified type name (e.g., 0x1::TestCoin::Coin) and the account address where the value of that type is stored (the account address stores module code and structural data). Although global storage is shared among all modules, each module has exclusive read/write access to its declared key (account address). This means that modules that declare a resource type can :

Post a value to global storage with the move_to<Coin> directive (e.g., line 14);

Removes a value from global storage with the move_from<Coin> instruction;

Get a reference to a value in global storage with the borrow_global_mut<Coin> directive (e.g., line 22).

Since the module “owns” the global storage entry that it controls by key, it can enforce constraints on that storage. For example, ensure that only ADMIN account addresses can hold structures of type 0x1::TestCoin::Info. It can do this only by defining a procedure (initialize) that uses move_to on the Info type and enforces the precondition for calling move_to on the ADMIN address (line 13). These constraints differ from static invariants in that they require run-time checking. In this case, since the parameter account is supplied at runtime, the programmer cannot statically force it to always be ADMIN, and thus requires an invariant check at line 13.

Here are the two static checking mechanisms that secure the module’s code: the invariant statute and the bytecode verifier.

a) Invariant Check (statute check)

Line 10 of the module, indicates the invariant of the static check – the sum of the value fields of all Coin objects in the system must be equal to the total_value field of the Info object stored in the ADMIN address. The term invariant is a term used in formal verification that denotes the conservation of a state, which can also be called invariant or invariant. We expect the constancy property to apply to all possible clients of the module (including malicious ones): any violation will break the integrity of Coin. Thus, invariants do not just affect individual objects, but a collection of them (i.e., all Coin objects). The place is actually the specification language that can be used for formal checks in move prover, which we will introduce in the next section.

b) Bytecode Verifier

Bytecode verifier: Safe types and linearization are the main scope of the bytecode verifier: As in this example, although other modules do not have access to the global storage unit controlled by 0x1::TestCoin::Coin, they can use this type in their own procedure and structure declarations. For example, another module could expose a payment procedure that accepts 0x1::TestCoin::Coin as input.

At first glance, modules that allow sensitive values such as Coins to flow out of the module that created them may seem dangerous – malicious client modules can create fake coins, artificially increase the value of coins they own, or copy/destroy existing coins. Fortunately, Move has a bytecode verifier (a type system enforced at the bytecode level) that allows module owners to prevent these undesired results. Only modules that declare the structure type Coin are allowed:

Create a value of type Coin (e.g., line 25);

“Unwrap” a Coin type value into its component field (in this case value);

Get a reference to the Coin field via a rust-style mutable or immutable borrow (e.g. &mut Coin).

This allows the module author to create values and field values for structures declared in the module. The validator also forces the structure to be linear by default. to ensure linearity in preventing copying and destruction outside the module in which the structure is declared (e.g., by overwriting a variable that stores the structure or allowing it to go out of scope). Also, the validator forces checks for some types of common memory problems (such as overflows).

There are three main types of testing processes:

Structure legal check: ensure the integrity of bytecode, detect illegal references, duplicate resource entities and illegal type signatures, etc.

Semantic detection of procedure logic: including parameter type errors, loop indexes, empty indexes and duplicate definition variables, etc.

Error on linking, illegal call to an internal procedure, or linking a process whose declaration and definition do not match.

The verifier will first create a CFG (Control-flow Graph). Since there is no non-linear logic, this control-flow graph can clearly describe the call relationships between program blocks without considering the recursion depth.

The verifier then checks the access range of the callee inside the stack to ensure that the contract callee cannot access the caller’s stack space. For example, when a procedure is executed, the caller first initializes the local variables inside the CallStackFrame and then puts the local variables inside the stack, assuming that the current stack height is n. Then the valid bytecode must satisfy the invariant: when the calling process ends, the stack height is still n. The validator mainly analyzes the possible impact of each instruction block’s instruction on the stack by The verifier ensures that no stack space of height higher than n is manipulated, mainly by analyzing the possible impact of each instruction block on the stack. One exception is that an instruction block ending in return must exit with a height of n + m, where m is the number of procedure return values.

At the same time, in order to check the type, each Value stack maintains a corresponding Type stack, and the Type stack is also popped and pushed with the instruction execution during execution.

Next is the resource check and reference check. Resource checking mainly checks constraints such as non-dual spend, non-destructible, and must have attribution (return value must be accepted) of resources. And reference checking combines dynamic and static analysis. Static analysis uses a borrow checking mechanism similar to the rust type system to ensure that: 1. all references must point to an already allocated store to prevent null pointers; 2. all references have secure read and write permissions.

The borrow_global call dynamically counts references to global variables, and the interpreter will determine each published resource and report an error if it is borrowed or moved.

Finally, there is a link check, which needs to be done again to check whether the linked objects and declarations match, the access control of the procedure, etc.

As you can see, the code is doubly secured at compile time by two mechanisms, invariant checking and bytecode verifier. Next, let’s see how MoveVM ensures runtime security by analyzing the runtime mechanism of move.

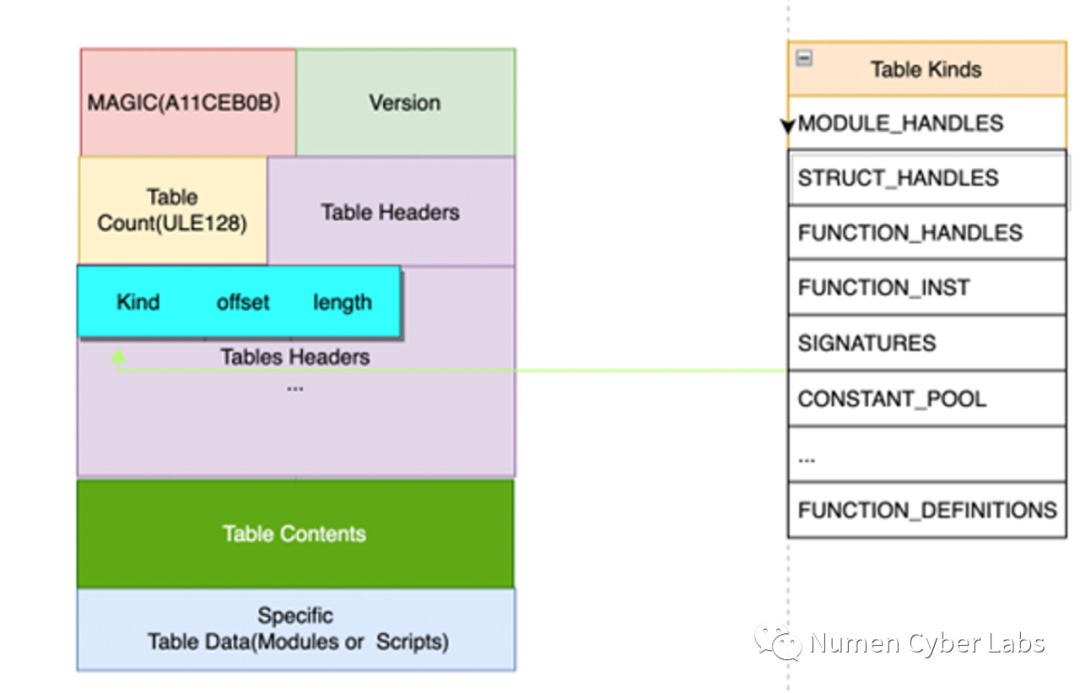

2. Move’s Running Mechanism

First, Move programs run in a virtual machine and do not have access to system memory at runtime. This allows Move to run safely in an untrusted environment and not be corrupted or abused.

Second, the Move program is executed on the stack. Formally, the previously mentioned global storage is divided into two parts: memory (heap) and global variables (stack). Memory is a first-order store, so its cells cannot be used to store pointers. Global variables are used to store pointers to memory cells, but they are indexed differently than memory. To access a global variable, the code provides an address and a type bound to that address. This division simplifies operations and makes the move language easier to formalize semantically.

While Move’s bytecode instructions are executed in a stack-based interpreter, the benefit of a stack-based virtual machine is that it is easy to implement and control, and requires less hardware environment, which is ideal for blockchain scenarios. At the same time, it is easier to control and detect copy and move between variables in a stack interpreter than in a register interpreter.

In the Move language, any value defined as a resource can only be moved destructively (invalidating the storage location where the value was previously saved), but only certain values (for example, integers) can be copied.

The Move program runs on the stack in a quadruplet of ⟨C, M, G, S⟩ consisting of:call stack (C), memory (M), global variables (G), and operands stack (S). The stack also maintains a function table (the module itself) to parse the instructions containing the function body.

The call stack contains all the contextual information about the execution of a procedure and the instruction number (instructions are uniquely encoded to reduce code size). When a procedure executes a Call instruction that calls another procedure, a new call stack object is created, and the corresponding call parameters are stored in memory and in global variables, and the interpreter starts executing the new contract’s instructions with it. When the execution process encounters a branch instruction, a static jump will occur inside the process. The so-called static jump actually means that the offset of the jump is determined in advance, and it will not jump dynamically like EVM. This is the feature of dynamic assignment which is not supported as mentioned before. This means that the dependency of the procedure within the module is acyclic, plus the module itself is not dynamically assigned, which strengthens the immutability of function calls during execution: the call frames of a procedure during execution are necessarily adjacent to each other, thus avoiding the possibility of re-entry. The final call to return ends the call, while the return value is placed at the top of the stack.

By studying the MoveVM code, we can clearly see that MoveVM separates the storage of data from the storage of the call stack (process logic), which is the biggest difference from EVM. For example, in EVM, to implement an ERC20 Token, the developer needs to write the logic and save the state of each user in a contract, while in MoveVM, the user state (resources under the account address) is stored independently and program calls must comply with permissions and mandatory rules about resources, which sacrifices some flexibility but gains a great improvement in security and execution efficiency (which helps to achieve concurrent execution).

3. Move Prover

Finally, let’s take a look at Move prover, a tool provided by Move that can assist with automated audits.

Move Prover is a formal verification tool based on deduction. It uses a formal language to describe the behavior of a program and uses deduction algorithms to verify that the program meets expectations. It can help developers to ensure that smart contracts are correct, thereby to reduce transaction risk. Simply, formal verification is the mathematical method to prove that our system is bug-free.

The major automatic software verification algorithm is based on the satisfiability module theories solver (SMT solver). Although the name looks a bit difficult to understand, SMT solver is actually a formula solver. The upper-level software verification algorithm splits its verification goal into some formulas, which are solved by SMT solver, and then further analyzes the results based on the solver’s results to report that the verification goal is valid or a counterexample is found.

A basic verification algorithm is deductive verification, but there are also a number of other verification algorithms, such as bounded model detection, k induction, predicate abstraction, and path abstraction.

It is the deductive verification algorithm that Move Prover uses to verify the program matched expectations. This means that Move Prover can deduce the behaviours of a program based on known information and ensure that it matches the expected behavior. This helps ensure that the program is correct and reduces the amount of manual testing work.

The general architecture of Move Prover is shown in the following diagram.

First, Move Prover receives a Move source file as input, which sets the program input specification. The Move Parser then extracts the specification from the source code, and the Move Compiler compiles the source file into bytecode, which together with the specification system is transformed into the Prover Object Model.

This model will be translated into a model called Boogie (also the name of the intermediate language). This Boogie code is passed into the Boogie verification system, which performs a “verification condition generation” on the input. The verification condition is then passed into a solver called Z3, a Satisfiability Theory (SMT) solver developed by Microsoft.

After the VC is passed into the Z3 program, this verifier checks if the SMT formula (whether the program code satisfies the specification) is unsatisfiable. If so, this means that the specification holds. Otherwise, a model that satisfies the condition is generated and converted back to Boogie format for issuing a diagnostic report. The diagnostic report is then generated to a source-level error similar to the standard compiler error.

To describe the specification system, move uses the Move Specification Language, which is a subset of the Move Language that supports for statically describing the behavior regarding program correctness without affecting original code. It can also stand alone as a .spec.move file, thus keeping operational code and formal verification code separate.

There are already many other tutorials about the Move Specification Language on the Internet, and the official documents is also elaborated. It is recommended that contract programmers learn more about it to improve the security of their code. At the same time, because the Move Specification Language can be written separately without importing into the original code, for projects with higher security requirements, the code should be assigned to a third-party security company with more security experience to write a more rigorous formal verification report while auditing the code.

Overall, Move Prover is a very useful tool to help developers ensure the correctness of smart contracts. It uses a formal language to describe the behaviour of the program and a deduction algorithm to verify that the program meets expectations. This helps reduce transaction risk and enables developers to deploy smart contracts into mainnet environments with more confidence.

4. Summary

The design of the Move language is excellent in terms of security considerations. It makes a very comprehensive consideration at the level of language features, virtual machine execution and security tools. The language features sacrifice some flexibility but force to type checking and linear logic which make automation and security verifiability in compilation checking and formal verification more easily. Meanwhile, MoveVM is designed to separate state from logic, which is more relevant to the needs of secure asset management on the blockchain.

In summary, at the language level, vulnerabilities such as re-entry, overflow, and Call/DelegateCall injection, revert attack commonly found in EVM and WASM can be effectively avoided, but issues such as authentication, code logic, and overflow in large integer structures (the latest version of the move language already supports u256, so overflow vulnerabilities do not arise if the official u256 type is used) cannot be avoided by relying on language-level features, and Move Prover does not work in the event of an overall careless oversight.

Although the Move language has taken a lot of consideration for programmers at the security level, there is no a completely secure language or a completely secure program in the world. We still recommend that developers of Move smart contracts use a third-party security company to audit their codes and write the specification language.